black walnut (Juglans nigra)

Juglandaceae, the walnut family

How to recognize black walnut. Look for large, alternately arranged, pinnately compound leaves with leaflets numbering 11-23 (or an even number, 10-22, as the terminal leaflet is often reduced or missing).

Black walnut in mid-June with immature fruits..

Flower and fruits. Like many forest trees, black walnut is monoecious, producing separate wind-pollinated pollen-producing (male) and ovule-producing (female) flowers on the same tree. The males are small and very numerous, borne in drooping elongate catkins, whereas the females are larger and occur in few-flowered clusters.

Black walnut flowers, males on the left, females on the right.

Walnut fruits are large “drupes”, i.e., single-seeded, surrounded by a fleshy non-splitting husk. Here’s what the walnuts look like after they’re fallen on the ground.

In the winter. Black walnut twigs are stout, with three-lobed leaf scars fancifully resembling monkey faces, and a true terminal bud. Inside, they have beautiful chambered pith.

Black walnut twigs have a true terminal bud, monkey-face leaf scars, and chambered pith.

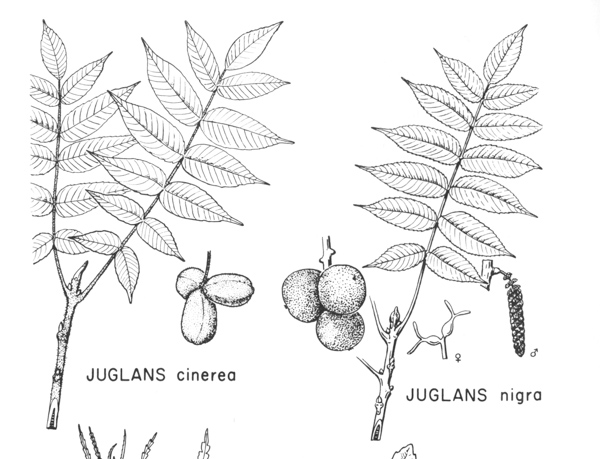

There’s a 2nd species of Juglans in Ohio, presented alongside black walnut (it’s rare so it would be good to get a search image for it) – butternut, Juglans cinerea. We can use leaf features and winter twigs to tell them apart. End leaflets are usually lacking in black walnut and present in butternut. Both species have large cream, wooly buds with large shield-shaped leaf scars that resemble “monkey faces”, but butternut has a hairy fringe at the top of the leaf scar, which is lacking in black walnut.

Where to find black walnut. E. Lucy Braun, in The Woody Plants of Ohio (1961, 1989; The Ohio State University Press) tell us that this species is “A tree of rich soil, almost always present in mixed mesophytic forest communities and frequent on high-level bottomlands”.

Scanned Image from an Old Book

(Flora of West Virginia, by P.D. Strausbaugh and Earl L. Core)

Oooh ooh. I have a question!

Why do gardeners recommend against planting veggies near a walnut tree?

Black walnut is often cited as being “allelopathic,” (literally meaning to make your neighbor sick). This an effect wherein the roots, leaves and fallen fruits produce a chemical–Juglone–that inhibits the growth of some plants, especially members of the tomato family. Allelopathy is seen as a means to minimize competition from other plants.